Reconciling concepts from FP and OOP

This post is part of the Advent of Haskell 2020 series. Hence, I tried to keep the content easy and enjoyable but still present some food for thought!

Some time ago I came across an interesting post on the Clean-Coder-Blog, which kept me busy for weeks until I finally decided to write this article.

In his blog-post Uncle Bob tries to reconcile concepts from both Functional Programming and Object Oriented Programming by explaining that both approaches are not mutually exclusive but both provide useful principles that go very well together and in fact are complementary:

In this blog I will make the case that while OO and FP are orthogonal, they are not mutually exclusive. That a good functional program can (and should) be object oriented. And that a good object oriented program can (and should) be functional.

He begins his argument by reducing FP and OOP each to a single central guiding principle in order to contrast the essential features of these two approaches as clearly as possible:

OOP condensed

He gives the following characterisation of OOP:

The technique of using dynamic polymorphism to call functions without the source code of the caller depending upon the source code of the callee.

With this short statement Uncle Bob points to the core of object orientation since its first incarnation in the Smalltalk language:

In an OO language a call of methods on a target object is dispatched based on the target object’s type, its class.

So a method call shape.draw() may invoke different code based on the class of the actual shape object:

The code of the draw method of class Rectangle may be different from the code in Circle.draw().

Client code will just call shape.draw(), not even knowing which actual Shape sub-class it’s working on. This kind of

polymorphism provides a very useful decoupling of clients from the target objects by using the methods of the baseclass Shape

as the API for all Objects inheriting Shape.

This mechanism allows to build elegant design like the Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern which is at the core of Smalltalks GUI and which influenced many similar designs in other OO-languages.

MVC is the seminal insight of the whole field of graphical user interfaces. I believe the MVC work was the first to describe and implement software constructs in terms of their responsibilities. I also believe that MVC was the first significant use of protocols to define components instead of using concrete implementations — each controller class had a certain set of messages it had to respond to, as did each view class, but otherwise there were no constraints on what they did and how they did it.

This quote conveys two major achievements of OOP:

- Decomposing software into separate components with distinct responsibilities

- Using protocols - APIs or interfaces in todays lingo - to decouple those components and allow for varying implementations.

It’s interesting to note that Uncle Bob does not consider Inheritance or Encapsulation to be the most important and central concepts in OOP.

FP boiled down

Next he gives a very brief characterization of functional programming:

Referential Transparency – no reassignment of values.

Referential transparency is implying purity as explained in the following definition from Wikipedia:

An expression is called referentially transparent if it can be replaced with its corresponding value (and vice-versa) without changing the program’s behavior. This requires that the expression be pure, that is to say the expression value must be the same for the same inputs and its evaluation must have no side effects.

The second part of Uncle Bob’s statement may be implied by this definition, but I prefer to see it as separate yet closely related principle, namely immutability:

In object-oriented and functional programming, an immutable object (unchangeable object) is an object whose state cannot be modified after it is created. […]

There is no FP vs OOP

After this dense characterization of the two programming paradigms Uncle Bob continues his arguments like follows:

The concepts of Polymorphism and Referential Transparency are orthogonal. You can have Polymorphism without Referential Transparency – and vice versa.

But orthogonality does not imply that both concepts are mutually exclusive. It is possible to have languages that support both Dynamic Polymorphism and Referential Transparency. It is not only possible, but even desirable to combine both concepts:

Dynamic Polymorphism is desirable as it allows building strongly decoupled designs:

Dependencies can be inverted across architectural boundaries. They are testable using Mocks and Fakes and other kinds of Test Doubles. Modules can be modified without forcing changes to other modules. This makes such systems much easier to change and improve.

Uncle Bob

Referential Transparency is desirable as it allows designs that are much easier to understand, to reason about, to change and to improve. It also allows designs that are much better suited for scalability and concurrency as the chances of race conditions etc. are drastically reduced.

Uncle Bob concludes that Dynamic Polymorphism and Referential Transparency are both desirable as part of software systems:

A system that is built on both OO and FP principles will maximize flexibility, maintainability, testability, simplicity, and robustness.

Uncle Bob

In the following sections I will have a look at the Haskell language to see how the principles of Ad-hoc Polymorphism and Referential Transparency are covered in our favourite language.

Ad-hoc Polymorphism and Referential Transparency in Haskell

Referential Transparency

Haskell is one of the rare incarnations of a purely functional language. So it goes without saying that Referential Transparency, Purity and Immutability are a given in Haskell. Yes, there are things like

unsafePerformIOorIORefbut overall it’s very easy to write clean code in Haskell due to the strict separation of pure and impure code by making side effects directly visibly in functions type signatures.Referential Transparency in Haskell is so much a given that it’s quite possible to apply equational reasoning to proof certain properties of Haskell programs. See for example the following Proof of Functor laws for the Maybe type. What’s remarkable here is that you can use the same language to write your code and to reason about it. This is not possible in languages that do not provide Referential Transparency and Immutability. To reason about programs in such languages you have to use external models like an abstract stack + register machine.

Ad-hoc Polymorphism

Being able to overload functions and operators with different implementations depending on the type of its arguments is called Ad-hoc Polymorphism. For example, the

+operator does something entirely different when applied to floating-point values as compared to when applied to integers. In Haskell, this kind of polymorphism is achieved with type classes and class instances.Haskell’s type classes are quite different from the classes in OOP languages. They have more in common with interfaces in that they specify a set of functions with their respective type signatures to be implemented by instance declarations.

A short case study

In this section I’m showcasing how these two concepts are supported in Haskell and how they can be combined without sacrificing FP principles.

Let’s have a look at a simple example that is frequently used in introductions to OOP:

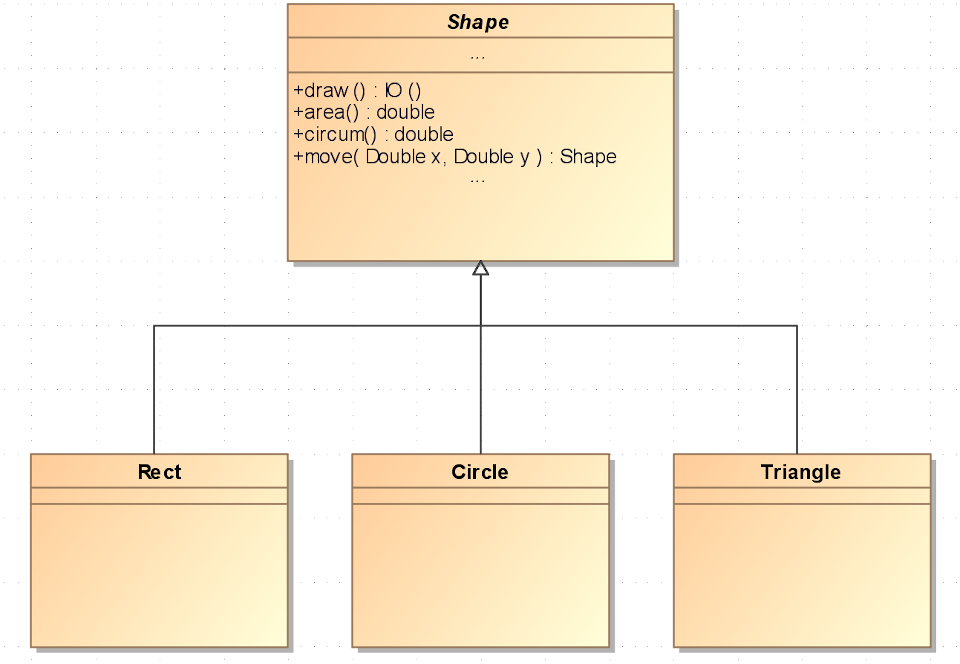

a class hierarchy representing geometrical shapes. In a typical OO language, we would

have an abstract base class Shape which specifies a set of methods, and concrete classes

Rect, Circle, Triangle, etc. which would implement specific behaviour.

This simple class hierarchy is shown in the following UML diagram:

In Haskell there is no inheritance between types. But with type classes we can specify an

interface which must be implemented by concrete types that wish to instantiate the type class. So we start with a

Shape type class:

-- | The Shape type class. It defines four functions that all concrete Shape types must implement.

class Shape a where

-- | render a Shape

draw :: a -> IO ()

-- | move a Shape by an x and y amount

move :: (Double,Double) -> a -> a

-- | compute the area of a Shape

area :: a -> Double

-- | compute the circumference of a Shape

circum :: a -> DoubleAny concrete type a instantiating Shape must implement the four functions draw, move,

area and circum.

We start with a Circle type:

-- | a circle defined by the centre point and a radius

data Circle = Circle Point Double deriving (Show)

-- | a point in the two-dimensional plane

data Point = Point Double Double

-- | making Circle an instance of Shape

instance Shape Circle where

draw (Circle centre radius) = putStrLn $ "Circle [" ++ show centre ++ ", " ++ show radius ++ "]"

move (x,y) (Circle centre radius) = Circle (movePoint x y centre) radius

area (Circle _ r) = r ^ 2 * pi

circum (Circle _ r) = 2 * r * pi

-- | move a Point by an x and y amount

movePoint :: Double -> Double -> Point -> Point

movePoint x y (Point x_a y_a) = Point (x_a + x) (y_a + y)As you can see, I’m not going to implement any real graphical rendering in draw but simply

printing out the coordinates of the centre point and the radius.

But at least area and circum implement the well-known geometrical properties of a circle.

Following this approach it’s straightforward to implement data types Rect and Triangle. Let’s start with

Rect:

-- | a rectangle defined by to points (bottom left and top right corners)

data Rect = Rect Point Point deriving (Show)

-- | making Rect an instance of Shape

instance Shape Rect where

draw (Rect a b) = putStrLn $ "Rectangle [" ++ show a ++ ", " ++ show b ++ "]"

move (x,y) (Rect a b) = Rect a' b'

where

a' = movePoint x y a

b' = movePoint x y b

area rect = width * height

where

(width, height) = widthAndHeight rect

circum rect = 2 * (width + height)

where

(width, height) = widthAndHeight rect

-- | computes the width and height of a rectangle, returns them as a tuple

widthAndHeight :: Rect -> (Double, Double)

widthAndHeight (Rect (Point x_a y_a) (Point x_b y_b)) = (abs (x_b - x_a), abs (y_b - y_a))There is nothing special here, we are just implementing the functions specified by the Shape type class

in a most simple way.

On to Triangle:

-- | a triangle defined by three points

data Triangle = Triangle Point Point Point deriving (Show)

-- | making Triangle an instance of Shape

instance Shape Triangle where

draw (Triangle a b c) = putStrLn $ "Triangle [" ++ show a ++ ", " ++ show b ++ ", " ++ show c ++ "]"

move (x,y) (Triangle a b c) = Triangle a' b' c'

where

a' = movePoint x y a

b' = movePoint x y b

c' = movePoint x y c

area triangle = sqrt (s * (s - a) * (s - b) * (s - c)) -- using Heron's formula

where

s = 0.5 * (a + b + c)

(a, b, c) = sides triangle

circum triangle = a + b + c

where

(a, b, c) = sides triangle

-- | computing the length of all sides of a triangle, returns them as a triple

sides :: Triangle -> (Double, Double, Double)

sides (Triangle x y z) = (distance x y, distance y z, distance x z)

-- | compute the distance between two points

distance :: Point -> Point -> Double

distance (Point x_a y_a) (Point x_b y_b) = sqrt ((x_b - x_a) ^ 2 + (y_b - y_a) ^ 2)

-- | provide a more dense representation of a point

instance Show Point where

show (Point x y) = "(" ++ show x ++ "," ++ show y ++ ")"Let’s create three sample instances:

rect :: Rect

rect = Rect (Point 0 0) (Point 5 4)

circle :: Circle

circle = Circle (Point 4 5) 4

triangle :: Triangle

triangle = Triangle (Point 0 0) (Point 4 0) (Point 4 3)Now we have all ingredients at hand for a little demo.

The type class Shape specifies a function draw :: Shape a => a -> IO ().

This function is polymorphic in its argument: it will take an argument of any type a

instantiating Shape and will perform an IO () action, rendering the shape to the console in our case.

Let’s try it in GHCi:

> draw circle

Circle [(4.0,5.0), 4.0]

> draw rect

Rectangle [(0.0,0.0), (5.0,4.0)]

> draw triangle

Triangle [(0.0,0.0), (4.0,0.0), (4.0,3.0)]This code makes use of Haskell’s Ad-hoc polymorphism and elegantly fulfils the requirements given for

Dynamic Polymorphism in Uncle Bob’s blog post:

“call functions without the source code of the caller depending upon the source code of the callee”. On the call site,

we just rely on the function draw :: (Shape a) => a -> IO (). This type signature assures us that it will work

on any concrete type a that instantiates the Shape type class.

By making use of the reversed application operator (&) we can create a more OOP look-and-feel to our code.

Depending on the context it may be more convenient to write and read code using (&) even when

you are not after an OOP look-and-feel.

> import Data.Function ((&))

> circle & draw

Circle [(4.0,5.0), 4.0]We can use the (&) operator to even work in a fluent api style:

main :: IO ()

main = do

rect

& move (4,2)

& draw

rect

& draw

circle

& move (4,2)

& draw

circle

& draw

-- and then in GHCi:

> main

Rectangle [(4.0,2.0), (9.0,6.0)]

Rectangle [(0.0,0.0), (5.0,4.0)]

Circle [(8.0,7.0), 4.0]

Circle [(4.0,5.0), 4.0]In Haskell all values are immutable: printing the original shapes a second time

demonstrates that operations like move are not destructive.

With this little setup we have shown that Haskell allows us to have both: Referential Transparency plus ad-hoc polymorphism. That is, we can use the essential elements of OOP and FP in one language. And: we are doing it all the time, as it’s quite common to use class types in this way.

Heterogeneous collections

In Haskell, container types like lists are polymorphic, but it is not possible to define a list like this:

shapes :: [Shape]

shapes = [circle,rect,triangle]because type classes are not types, but constraints on types.

So in haskell a list like [circle,rect,triangle] is considered to be heterogeneous, as the concrete

types of all the elements differ.

There are several ways to have heterogeneous collections in Haskell.

I will demonstrate just one of them, which is based on existential types.

(I have chosen this approach as it keeps the code easier to read and allows to add more Shape types whenever needed.

There is also a recent blog post on Existential Haskell which demonstrates some interesting use cases for existential types.

However, the sourcecode for this example also demonstrates a solution based on a simple sum type.)

Once we activate the ExistentialQuantification language extension, we can define a data type

ShapeType with a single constructor MkShape that will take any instance of a concrete type

instantiating the Shape type class:

{-# LANGUAGE ExistentialQuantification #-}

data ShapeType = forall a . (Show a, Shape a) => MkShape aNow we can make ShapeType an instance of Shape which will delegate all function calls to

the wrapped types:

instance Shape ShapeType where

area (MkShape s) = area s

circum (MkShape s) = circum s

draw (MkShape s) = draw s

move vec (MkShape s) = MkShape (move vec s)

-- we also have to manually derive a Show instance as auto deriving is not possible on the existential type

instance Show ShapeType where

show (MkShape s) = show sWith this setup we can define a list of shapes as follows:

shapes :: [ShapeType]

shapes = [MkShape rect, MkShape circle, MkShape triangle]Finally, we are able to use this list just as any other:

main :: IO ()

main = do

print $ map area shapes

print $ map circum shapes

print $ map (move (4,10)) shapes

putStrLn ""

mapM_ draw shapes

-- and then in GHCi:

> main

[20.0,50.26548245743669,6.0]

[18.0,25.132741228718345,12.0]

[Rect (4.0,10.0) (9.0,14.0),Circle (8.0,15.0) 4.0,Triangle (4.0,10.0) (8.0,10.0) (8.0,13.0)]

Rectangle [(0.0,0.0), (5.0,4.0)]

Circle [(4.0,5.0), 4.0]

Triangle [(0.0,0.0), (4.0,0.0), (4.0,3.0)]Conclusion

In our short Demo we have seen that Haskell supports both Referential Transparency and Polymorphism.

We have also seen that the reversed application operator (&) allows us to structure code in a way that even has some

kind of OOP look-and-feel while remaining purely functional.

If we follow Uncle Bob’s argumentation to view Polymorphism to be the central concept of OOP (and in consequence regard other important OO features like Inheritance or Encapsulation as not so distinctive), we can conclude that Haskell is already well prepared to implement programs in the hybrid way proposed by him.

In fact, the benefits associated with this approach (flexibility, maintainability, testability, simplicity, and robustness) are typical key features of systems implemented in Haskell.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to David Feuer for helping me with a stupid error in the existential type code!

Thanks to the Advent Of Haskell 2020 team for having this blog post in their advents calendar!